記無常簿

簡繁轉換 - 繁體

林鈺堂

一九八八年二月十日,我想到如果我把親見過而已亡故的人全記在一處,對於我這個全力在修行的人,應該有警惕無常的作用。我在抽屜裡找到一小本藍色封面的一九八七年按日記事簿,我就利用這本完全未用而過時的簿子。我先在首頁題名「無常簿」,然後在逐日的空格裡,填入我憶起的名字。

隨著一個一個的名字,浮起一件一件的往事。有的名字已經記不得了,就記下親屬關係的稱謂;有的並不知道名字,就記下簡單的描述;有的還沒有名字就已經走了。有的只有一面之緣;有的曾經多年共處。有的是千里外突來的耗音;有的是面前逐日的告別。有急病去的;也有久病亡的。有因學業問題而自殺的;也有因婚姻不如意而自盡的。有為了生意上的糾紛而被殺的;也有為了男女間的恩怨而被害的。有的胎死;有的早夭;有的含苞即亡;有的英年遽逝;有的老病交迫而去;有的無疾長命而終。四十一歲的我,一個人,就親見了這麼樣形形色色的無常例子。

面對這無常的事實,想起世界上時時刻刻有千千萬萬的人走了,我很直覺地體會到,世間的是非紛爭無意味。多麼希望能利用這短暫寶貴的一生,好好地來做些積極的貢獻。

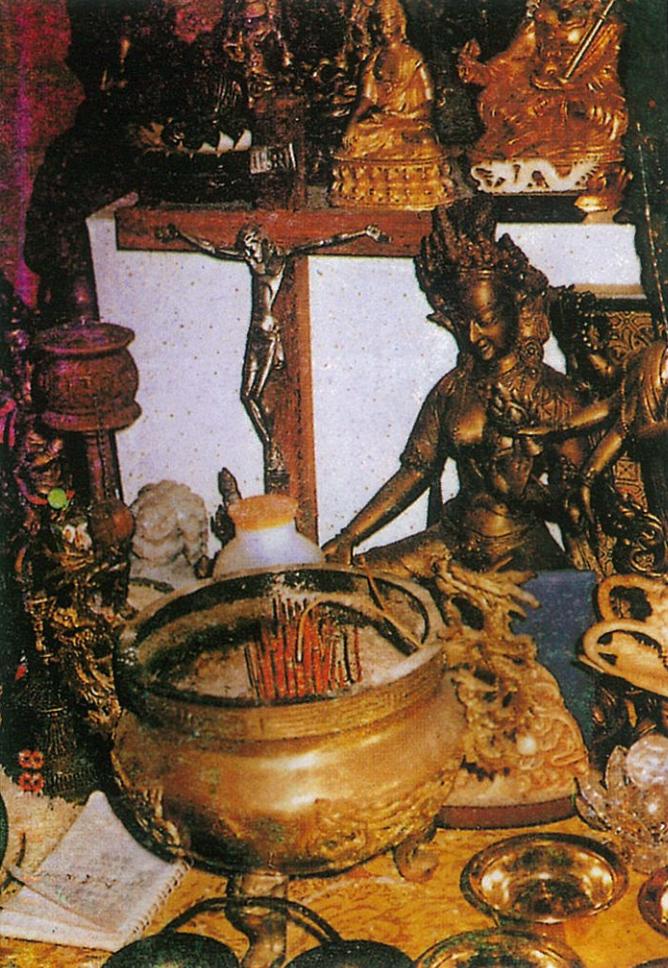

我把這本無常簿展開立在佛桌上,靠著觀世音菩薩化身綠度母的蓮座,並且上香祈禱這些亡者可以得到佛菩薩的加被,特別是度母的救渡,早日脫離輪迴苦海。

當晚將入睡時,意念方沈寂,忽然覺查自己原有輕微的「死亡不是我會有的問題」的妄念。這種妄想是我們一般人可能潛存的自欺,因為死亡似乎離現實日常生活非常遙遠。今天我面對著無常的實例,無意中突破了原有的妄念。妄念深藏在我們的意識中,籠罩著我們,所以不易查覺,只有在突破之時,才能一瞥其貌。

接著又直覺地體會到,死時得與世間的一切都分開。這是誰都意想得到的,但是由自己內心深處生出這樣的認識卻不是我曾有的。我們平時就要練習萬事不掛懷,免得臨終痛苦。從臨終之時回顧,我們一生為太多無謂的小事牽腸掛肚,太不值得!遇到心中煩惱糾纏,我就想:如果我現在臨終,我為這些事煩惱,我這一生值得嗎?這樣一想,往往就把我從煩惱中拉出來,煩惱就消失了。

第二天早上發現,昨晚上香祈禱的那柱線香,完全燃盡而未斷,並且香頭指向綠度母表示救渡而下垂的右手。我拍下照片附在本文之後,相片中還可見到藍色的無常簿就在度母座下。這樣感應想是佛菩薩慈悲攝受這些已逝的眾生,並且讚許記無常簿的修法吧!

從那天以來,我繼續在記無常簿。遇到有人請我為亡者修超度的密法,我也把亡者的名字加入。雖無親識之緣,卻有修法之緣,何況是修渡亡之法,更能警惕無常之現實、迅速而難以預測。有些後來加入的名字,是因為偶然憶起再補記的。可見無常雖現實,我們事未臨頭,就容易忽略忘去。藉記無常簿使無常成為我們心中常有的一件事,免得我們為無意義的俗世而沈迷受苦,使我們有清新的心地可以培植善念,發為積極的善行。

我們學算術,不但要做習題,並且要會應用在日常生活中的買賣上。記無常簿,不止是練習佛陀教示的「觀無常」,並且應用到我們自身的經驗裡,使我們得益。理論與實踐配合,我們才能真正得受用。因為所記的是親歷的活生生的例子,所以對我們有莫大的衝擊與說服力。我初記當晚的體會,便是個好例子。

佛法中修無常有許多方法,例如觀死(觀死之必來、死期之不可測、死時之孤立無助,等等)、觀心念之遷滅、他人臨終助念佛號、以及去尸林念佛超幽。記無常簿可以做為這些方法的加行,並且簡單易行。平常安放此簿於佛桌上,使亡者得佛佑,行者也藉之兼修慈悲心;又因為不論緣之深淺,都平等記下,所以也包含了平等大悲的修習在內。

希望大家都試行此法,同蒙法益!

|

|---|

Keeping a "Record of Impermanence"

Dr. Yutang Lin

On February 10, 1988 it occurred to me that keeping a record of the names of all those deceased people whom I had met in person would help awaken in me a keen sense of impermanence. To a full-time Buddhist practitioner like me it would be very beneficial. I found a small blue-covered 1987 daily notebook in my drawer, so I made use of this unused but outdated notebook. On the first page I entitled it A Record of Impermanence and in the daily blank I filled in names that I remembered.

As I put down each name, past events began to emerge in my mind one by one. There were some whose names were no longer remembered, so instead I put down a name for the relationship; some whose names were unknown to me, so I put down a brief description; and some even passed away before they were named. Some I met only once; some I was with for years. Some whose death came as a surprise from thousands of miles away; while others' were a gradual daily face-to-face good-bye. Some died of sudden illness; while others died of lingering sickness. Some committed suicide because of difficulty in school; while others because of an unhappy marriage. Some were murdered by business partners; while others were killed by romantic competitors. Some died in the womb; some died in infancy; some died a teenager, like a flower in bud; some died suddenly in their prime years; some died in the snare of old age and sickness; some died in the quietness of a long and peaceful life. At age forty-one I, as just one individual, had witnessed such a vast variety of cases of impermanence.

Facing the fact of impermanence and considering that every moment there are thousands of people passing away, I intuitively realized the futility of worldly arguments and competitions. How I wished to use such a transient and precious life-time to offer some positive contributions to the world!

I put this Record of Impermanence, with its pages open, on the altar near the lotus seat of Green Tara—a transformation of the great compassionate Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guan Yin). I lit an incense stick and prayed that these deceased ones would be blessed by Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, especially by the Green Tara, and thereby attain liberation from the sufferings of transmigration.

That night, just before I fell asleep, as my thoughts had quieted down, suddenly I sensed that I had held a subtle delusive thought in the past that death was not my problem. Such a delusive thought might well be present in the minds of many of us without our realizing its presence. After all, death seems to be so distant from the reality of our on-going daily life. Earlier that day I came to face the concrete cases of impermanence and thereby unintentionally shattered the delusive thought I had carried. Delusive thoughts are hiding deep down in our consciousness and obscuring our perspectives, hence they are hardly recognizable. Only at the moment of their shattering can we get a fleeting glimpse of them.

Immediately following this intuitive realization came another: At the moment of death we are to separate from everything in the world. This may be obvious to anyone who reflects on death; nevertheless, I had never had such an awareness arising from the depth of my mind. We need to practice being detached from all things lest we suffer at the end. Otherwise, as we look back, at the moment of death, we will realize that our lives have been infested with worries and quarrels over insignificant trivialities. What a waste it is! Whenever I am entangled by sorrows in my mind I would think: If this is the final moment of my life and I am entangled by these matters, would my life be worthwhile? Such a reflection usually pulls me right out from my sorrows, and the sky looks blue and sunny again!

The next morning I discovered that the incense stick I had lit and offered for my prayer, although completely burned, remained whole with its body turning in a recurving way and its head pointing toward the right hand of the statue of Green Tara. Her right hand extends downward with an open palm, signifying her salvation activities. I took a picture of it and the photo is reprinted at the end of this article. In this photo the blue cover of my Record of Impermanence can be seen at the seat of the Green Tara. To me, this inspiring occurrence indicated Buddha's compassionate blessing in answer to my prayers for the deceased ones, and approval of the practice of keeping a Record of Impermanence.

Since that day I have continued to keep my records of impermanence. Whenever people ask me to do Powa (a Buddhist tantric practice to transfer the consciousness of deceased ones to the Pureland of Buddha) I also enter the name of the deceased in my book. Although I had not met all of them in person, by doing Powa for them I established a wonderful Dharma connection. Besides, Powa is for the benefit of the deceased ones, and naturally reminds us of the reality of impermanence, of its immediacy and unpredictability. (By the way, sometimes when I did Powa for deceased people, I saw them appear before me.) Some of the names in the record were entered sporadically later because only then they sparked my memory. This shows that although impermanence of life is a reality, nevertheless, in our normal daily life it is very easy for us to neglect and forget about it. The practice of keeping a Record of Impermanence would constantly remind us of the reality of impermanence, lest we indulge ourselves in insignificant worldly pursuits and suffer from resulting turmoil. It would help safeguard the purity and freshness of our minds so that wholesome ideas would sprout and grow into kindness and compassionate activities.

To learn arithmetic thoroughly we should not only be able to do exercises in the book but also be able to apply it in real-life situations. Keeping a Record of Impermanence is not only to practice Buddha's teaching of being mindful of impermanence but also to connect the teaching with our personal experiences to benefit us on a down-to-earth level. Only by unifying the theoretical with the practical can we actually receive the essence of Buddha's teachings. Since the cases of impermanence that we put into writing are ones that we have actually witnessed, been personally involved in, and even suffered for, they have tremendous impact on us and carry with them supreme power of persuasion. My awakening to the presence of delusive thoughts in me is a good example of the effectiveness of this practice.

There are many practices of impermanence in Buddhism. For example, meditations on death (to meditate on the certainty of death's arrival, the unpredictability of the time of death, one's helplessness and loneliness at the moment of death, etc.), observation on the changing scenes of our mental activities, chanting Buddha's name near someone who is passing away, and visiting cemeteries to pray for the dead. Keeping a record of impermanence can be an easy but helpful addition to the other practices. This record is to be placed on the altar so that the deceased ones are under the blessing of Buddha and thereby we may practice an act of great compassion. As we write down the names, we do not distinguish between friends or foes, family members or acquaintances; therefore, it is also a practice of equal-love-for-all.

I hope that everyone who reads this article will adopt this practice and thereby share its effective benefits.

Originally written in Chinese on April 4, 1988

Chin-Ming Festival, the Chinese Memorial Day

Translated on May 8, 1992

both in El Cerrito, CA, U.S.A.

[Home][Back to list][Keeping a "Record of Impermanence"]